They called my mom's death at 9:26 am, but it was really more like 9:24.

It was so damn cold in the room. Though it was scheduled to be another scorcher—the previous days had been some of the hottest that summer, in the high 90s—I was bundled in an old purple sweater on a plastic chair that was already making my back hurt. That morning, I had burst out of bed, jumped into the first clothes I found, stuffed a bowl of cereal in my face and thrown together a totebag with a strange assortment of items, like I was going on some morbid sleepover: Keys. Wallet. Phone. Charger. Bottle of water. Secondhand copy of Orange is the New Black. NYT crossword puzzle book that I bought during her first hospital visit in 2010, and that had been a witness to the entire ordeal.

She had already spent the previous night dying. In the late afternoon the day before, they told us she wasn't coming through this time. My dad and I told the nurses that she never wanted extraordinary measures taken to prolong her life, and they moved her up to the fifth floor—the "comfort care" floor. We went to the Taco Bell across the street while they readied her and had the most unappealing meal of our lives. When we returned, we found her in a quiet, private room, lit only by a sunset settling over the Santa Cruz mountains. It was so beautiful. Too beautiful. Downright corny; almost mocking.

My dad called everyone that needed to know (a small group; my mom didn't have many people she was close to) and one by one they all came. We sat in a circle on the plastic chairs and told stories of her life late into the night. At one point, her friend, her one and only friend, was lingering over her. "Don't you want to sit here and hold your mommy's hand?" she said to me.

I didn't.

An Incompatible Relationship

All my friends seem to have gone on to have these cute, cozy relationships with their respective moms. They brunch on weekends; they're friends with them on Facebook. And even though they sometimes talk during movies or ask stupid questions about iPhones, they're still . . . friends. Good friends. Best friends, even.

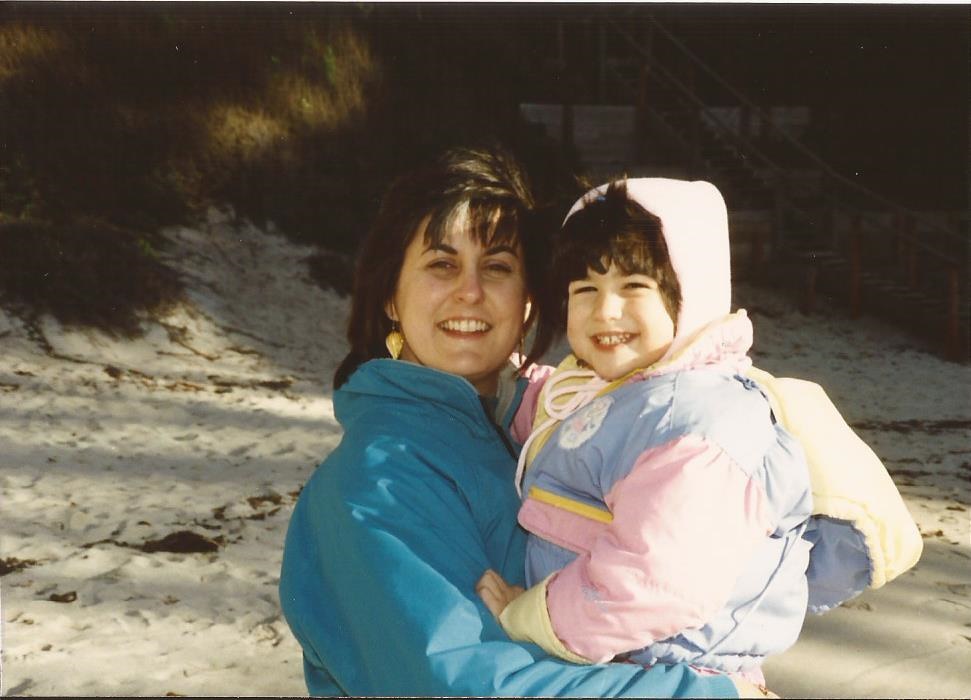

To me, being friends with your mother is a bizarre concept, because the truth is, my mom and I never had a great relationship. I feel terrible admitting that—some people have shitty moms; some people have no mom at all, and for God's sake, she just died—but we honestly were not compatible people.

My mom was, on the outside, just a shy, simple girl. She didn't have many interests that she developed herself—most of her interests were ones she enjoyed by proxy, through my father. She was what we today might call basic. But she also . . . wasn't. She got her degree in political science, and in the turbulent '70s, no less. She was, shall we say, firm in her beliefs—and she had some pretty progressive ones for an Italian-Catholic girl. She believed in human rights for minorities of all stripes, and hated war more than anything else. She was pro-choice before it was cool.

But instead of raising hell like she should have, she settled into life as a secretary and mother pretty easily (in reviewing albums of old photos these last few months, I've seen the feathered hair and floral maxis give way to button-downs and mom jeans rather abruptly). She didn't have many things that excited or interested her, and she had a tendency to close herself off from relationships.

She also had a tendency to fly off the handle. Some of my earliest memories are of her crying on the bed in her room, moaning, "You hate me; you think I'm a terrible mother." (I was four. I didn't even know what that meant.) When my period came the day of the sixth grade end-of-the-year trip to the water park, she stood in the door of the bathroom and screamed at me because my very first tampon insertion was making her late for work. When I accidentally left my copy of My Side of the Mountain in my desk in 4th grade and thus could not complete the homework, she ended up wailing at me about how I was going to end up a destitute bum with no job or insurance, "who has to beg doctors to treat their children." The older I got, the more I started to walk on pins and needles around her. I never knew what would set her off. Hearing her key in the door in the afternoon turned my stomache in knots.

It all hit a fever pitch in high school, when she made every attempt to exercise complete control over my school life. We're not talking tiger mom-level shit, but she busied herself with keeping a constant watch over my homework, and "checked" it when I was done (i.e. she ended up doing it for me if she didn't think it was good enough) well into my teen years. In my later teen years, she was looting my backpack for homework I hadn't reported to her and making me get weekly grade reports from my teachers—and if I didn't, she'd pester them by phone and e-mail until they complied. She also found and read my diary, and told me this one day like it was NBD.

I eventually lost my patience. At least twice a week, we'd end up screaming ourselves hoarse. It's not like I didn't provoke her, but even now, much of her behavior seems out-of-control; damaging. I moved away to college in 2004, and an unspoken, rarely-acknowledged rift sat wedged between us up until the very end. For a long time, I wrestled with the fact that my mom and I might never be close.

What I Learned When She Left Me

Almost as soon as she died, people started telling me, "Oh, she was such a strong woman." To which I wanted to snap back, "No, she wasn't." But in the aftermath of her passing, I've come to realize that she was stronger than I thought.

My mother was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis, which ended up taking her life, several years before I was born—and type 1 diabetes almost a decade before that. I wonder now if her life wasn't so much basic, as pragmatic. Why try to do anything extraordinary when the rug could be pulled out from under you at any minute?

And then there's the matter of her upbringing. In the 27 years I knew her, she mentioned it once or twice, saying only that her father was "emotionally and verbally abusive." Sure, it was a different time (Don Draper's not a model parent, after all) but after she died, a few stories about her father exploding with rage over minute accidents—one of them was literally spilled milk—came to light.

Now that it's all over, I can see the truly Shakespearean scope of her life: beaten down emotionally by her father and saddled with precarious health; lifted out of what could have been complete despair by my dad, only to be struck with a death sentence. It's a short walk from an emotionally abusive father and battling a deadly disease to blowing a gasket over simple childhood mistakes.

Now that it's all over, I can see the truly Shakespearean scope of her life: beaten down emotionally by her father and saddled with precarious health; lifted out of what could have been complete despair by my dad, only to be struck with a death sentence. It's a short walk from an emotionally abusive father and battling a deadly disease to blowing a gasket over simple childhood mistakes.

She was maybe the best mom she knew how to be.

Near the end, she started saying I love you. She was 60 years old and in a nursing home by then, and I'd taken up a schedule of after-work visits to help distract her from the fact that she was, well, 60 years old and in a nursing home. Things were good—for the first time, I deeply enjoyed talking to her. I'd tell her about my day, and even if I didn't have anything to say, I'd just sit and watch the news with her. I can't tell you how good it felt, when she was lucid, to finally talk to her like an adult. When something funny or annoying or altogether new happened to me, the first thing I would think was, "I can't wait to tell this to mom." It felt even better when I got a jargon-filled document at work that I couldn't comprehend, and I'd bring it to her because she was a secretary, and also because moms always know what to do.

After my evening visits, I'd gather my things and head for the door. Sometimes, as I reached the threshold, she'd blurt, "I love you." The first few times it was awkward. The words tumbled out clumsily, dissolving into the din of the understaffed nursing facility. I would take a breath and say it back, then scurry out the door. And we would never speak of it again, until the next time. Sometimes I'd be crying when I said it, sometimes she'd be crying when she said it, but we kept on saying it. It never felt totally natural, but it got easier every time.

Just like her, I've always kept my emotions on lockdown—if you want to know me, you kind of have to work for it. I even made my mom work for it. For a long time, I felt like it made me a monster, but it took me until very recently to realize that two people don't have to like each other to love each other. I still, to this day, don't know how to reconcile our rocky relationship with the truth that she truly loved me.

All I know is that in those last few seconds, after we noticed she had stopped breathing and my dad went to get the nurses, all I could think to say was, "I love you."